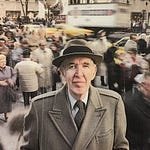

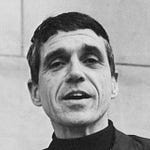

It is slightly jarring to find the radically-minded Paul Goodman a welcome guest on the September 12, 1966 episode of William F. Buckley’s Firing Line television show. The topic was “Are Public Schools Necessary?”, to which Goodman responds in the negative—or at least with an alternative vision of small, decentralized schools that emphasized experience in the real life of the neighborhood over stultifying curricula in quarantined classrooms.

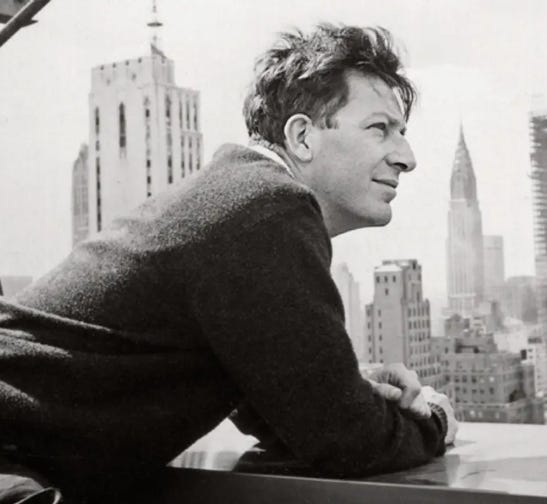

By this time, Goodman was at the height of his fame as an oracle of the New Left and the 60s student movement, a speaker so popular that students at San Francisco State raised a year’s salary for him to come teach there. He was also in his mid-fifties.

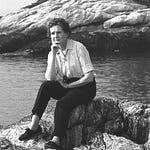

Beginning in the Depression years, Goodman had poured forth novels, short stories, poetry and essays with great elan, despite a peripatetic existence caused by periodic sexual indiscretions. (Some of these incidents were just the result of the era’s bigotry, as Goodman was an unapologetic bisexual; other incidents would still be considered quite problematic today.)

A radical Freudian at first, Goodman became increasingly interested in the work of Fritz and Laura Perls, even co-authoring with them the first text on Gestalt therapy in 1951. His unpopular pacifist stance during the Second World War complicated his career and by the late 1950s, Goodman was continuously struggling to support a wife and two small children.

Then came an offer to write a book giving his solutions to the issue of the day, juvenile delinquency, as it was then quaintly called. His Growing Up Absurd (1960) was a cultural phenomenon, not least because Goodman blamed society itself, not young people, for the latter’s widespread sense of alienation. Published early in a moment of growing social upheaval—the rising Civil Rights movement, deepening involvement in Vietnam, the Free Speech Movement at UC Berkeley—the book became an omnipresent bible of student rebellion, selling hundreds of thousands of copies.

And despite the famous catchphrase of the times, “never trust anyone over thirty” (which Goodman certainly was), the more radical students on campuses across the country not only trusted him—practically alone among adults in these years—but flocked to hear his every word.

One of those students—who actually met and spoke with Goodman—was our guest for this episode, Gregory W. Knapp, now a professor emeritus at the University of Texas at Austin.

Greg received his BA from the University of California, Berkeley, in Mathematics and Economics, and his PhD in Geography from the University of Wisconsin. His research has focused on themes in cultural and regional geography. We were intrigued by Greg’s article, “Kenneth Rexroth and Paul Goodman: Poets, Writers, Anarchists and Political Ecologists” which inspired us to invite him on the show.

Some key takeaways from our conversation:

A jack of all trades, Susan Sontag compared Goodman to Emerson, describing him as “a connoisseur of freedom.” A novelist, poet, lay psychiatrist, social scientist, urbanist, and practitioner of the now-lost art of being a “man of letters”

Goodman was perhaps the best writer on the theme that launched the 1960s counterculture: our social world in its current arrangements is not worth “adjusting” yourself to. (This made Goodman a “reverse Don Quixote”, as one of his reviewers remarked, the only sane man amidst a crazy world.)

He was an exponent of a kind of “revolutionary hope” which all but vanished after the Vietnam War.

Goodman knew conforming was madness but that fully dropping out was also mad—he wanted a sane alternative. As critic George Steiner put it, Goodman was “trying to hack out elbow room for the imagination”—our lost genius for imagining bold solutions to problems.

Life over theory and any ideas that reify Society: Against the jargon-ridden state of most academic writing, Goodman deliberately wrote to reach the largest possible educated audience.

Goodman was an early reader of Peter Kropotkin, which led to a lifelong love affair with community anarchism in an anti-Marxist frame—but he cared about “citizenliness.”

Like his good friend Ivan Illich, Goodman was a deep critic of education as merely “learning the code,” a way of keeping the young safely out of the labor market for 16 years.

Goodman told Studs Terkel: “I might seem to have a number of divergent interests…but they are all one concern: how to make it possible to grow up as a human being into a culture without losing nature. I simply refuse to acknowledge that a sensible and honorable community does not exist.”

In his 1967 Massey Lectures, he said: “The question is whether or not our beautiful libertarian, pluralist, and populist experiment is viable in modern conditions. If it’s not, I don’t know any other acceptable politics, and I’m a man without a country.”

Timestamps:

[02:30] Pete describes discovering Goodman, a true public intellectual who worked across multiple disciplines, through the documentary Paul Goodman Changed My Life.

[11:00] Discussion of Goodman's early life in New York City and how the city itself strongly influenced his worldview

[14:00] Goodmans’s time at City College of New York, where he developed his commitment to community anarchism through reading Kropotkin; his early career as a writer and intellectual

[31:30] Goodman’s anarchist philosophy, which focused on drawing lines to keep society's conforming impulses at bay and create free spaces for natural instincts and authentic living

[41:00] Reflections on Goodman’s breakthrough book Growing Up Absurd (1960) and its critique of how modern society fails to provide meaningful opportunities and worthwhile goals for young people to grow into

[52:30] Goodman’s work in psychology and as a co-founder of Gestalt therapy, which focused on helping people live authentically rather than adjusting to society's demands

[1:14:30] How Goodman became alienated from the militant radicals of the late 1960s as he critiqued their growing cynicism while maintaining his faith in humanism

[1:41:00] Interview with Gregory W. Knapp, who met Goodman at Berkeley in the 1960s and provides firsthand accounts of Goodman's interactions with students and his impact on the counterculture

[2:19:00] Final reflections on Goodman's legacy: how some of his ideas about authenticity and personal freedom became mainstream while his vision of participatory democracy and community remains unfulfilled

Recommended:

Paul Goodman Changed My Life (2011 documentary)

Communitas (1947)

The Empire City (1959)

Growing Up Absurd (1960)

Compulsory Miseducation (1964)

“Are Public Schools Necessary?”, Goodman as guest on William F. Buckley’s Firing Line (Sept. 12, 1966)

Like a Conquered Province—Massey Lectures (1967)

New Reformation (1970)

Kenneth Rexroth and Paul Goodman: Poets, Writers, Anarchists and Political Ecologists, Gregory W. Knapp (2021)

On Paul Goodman, Susan Sontag in The New York Review (1972)

Many thanks to the great band NOBLE DUST, who provides the music for Lost Prophets. Their latest album, A Picture for a Frame, is here.

Many thanks to our editor, the great Dan Thorn.

LOST PROPHETS is a podcast about the mid-century voices of solidarity we need to hear again. To listen on your podcast player, our Spotify link is here, Apple Podcasts link is here, and RSS link is here.